The Complete Program

The complete program including crc checks is:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <bcm2835.h>

uint8_t crcCheck(uint8_t msb, uint8_t lsb, uint8_t check);

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

if (!bcm2835_init())

return 1;

bcm2835_i2c_begin();

bcm2835_i2c_setClockDivider(BCM2835_I2C_CLOCK_DIVIDER_626);

setTimeout(40000);

bcm2835_i2c_setSlaveAddress(0x40);

char buf[4] = {0xE3};

uint8_t status = bcm2835_i2c_read_register_rs(buf, buf, 3);

printf("status=%d\n\r",status);

uint8_t msb = buf[0];

uint8_t lsb = buf[1];

uint8_t check = buf[2];

printf("msb %d \n\r lsb %d \n\r checksum %d \n\r", msb, lsb, check);

printf("crc = %d\n\r", crcCheck(msb, lsb, check));

unsigned int data16 = ((unsigned int) msb << 8) | (unsigned int) (lsb & 0xFC);

float temp = (float) (-46.85 + (175.72 * data16 / (float) 65536));

printf("Temperature %f C \n\r", temp);

buf[0] = 0xF5;

bcm2835_i2c_write(buf, 1);

while (bcm2835_i2c_read(buf, 3) == BCM2835_I2C_REASON_ERROR_NACK) {

bcm2835_delayMicroseconds(500);

};

msb = buf[0];

lsb = buf[1];

check = buf[2];

printf("msb %d \n\r lsb %d \n\r checksum %d \n\r", msb, lsb, check);

printf("crc = %d\n\r", crcCheck(msb, lsb, check));

data16 = ((unsigned int) msb << 8) | (unsigned int) (lsb & 0xFC);

float hum = -6 + (125.0 * (float) data16) / 65536;

printf("Humidity %f %% \n\r", hum);

bcm2835_i2c_end();

return (EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

uint8_t crcCheck(uint8_t msb, uint8_t lsb, uint8_t check) {

uint32_t data32 = ((uint32_t) msb << 16) |

((uint32_t) lsb << 8) |

(uint32_t) check;

uint32_t divisor = 0x988000;

int i;

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

if (data32 & (uint32_t) 1 << (23 - i))

data32 ^= divisor;

divisor >>= 1;

};

return (uint8_t) data32;

}

void setTimeout(uint16_t timeout) {

volatile uint32_t* stimeout = bcm2835_bsc1 + BCM2835_BSC_CLKT / 4;

bcm2835_peri_write(stimeout, timeout);

}

Of course this is just the start.

Once you have the device working and supplying data it is time to write your code in the form of functions that return the temperature and the humidity and generally make the whole thing more useful and easier to maintain.

This is often how this sort of programming goes - at first you write a lot of inline code so that it works as fast as it can then you move blocks of code to functions to make the program more elegant and easy to maintain checking at each refactoring that the programming still works.

Where Next

Not all devices used standard bus protocols. Next we looks at a custom serial protocol that we have to implement for our selves..

Now On Sale!

You can now buy a print or ebook edition of Raspberry Pi IoT in C from Amazon.

For Errata and Listings Visit: IO Press

This our ebook on using the Raspberry Pi to implement IoT devices using the C programming language. The full contents can be seen below. Notice this is a first draft and a work in progress.

Chapter List

-

Introducing Pi (paper book only)

-

Getting Started With NetBeans In this chapter we look at why C is a good language to work in when you are creating programs for the IoT and how to get started using NetBeans. Of course this is where Hello C World makes an appearance.

-

First Steps With The GPIO

The bcm2835C library is the easiest way to get in touch with the Pi's GPIO lines. In this chapter we take a look at the basic operations involved in using the GPIO lines with an emphasis on output. How fast can you change a GPIO line, how do you generate pulses of a given duration and how can you change multiple lines in sync with each other? -

GPIO The SYSFS Way

There is a Linux-based approach to working with GPIO lines and serial buses that is worth knowing about because it provides an alternative to using the bcm2835 library. Sometimes you need this because you are working in a language for which direct access to memory isn't available. It is also the only way to make interrupts available in a C program. -

Input and Interrupts

There is no doubt that input is more difficult than output. When you need to drive a line high or low you are in command of when it happens but input is in the hands of the outside world. If your program isn't ready to read the input or if it reads it at the wrong time then things just don't work. What is worse is that you have no idea what your program was doing relative to the event you are trying to capture - welcome to the world of input. -

Memory Mapped I/O

The bcm2835 library uses direct memory access to the GPIO and other peripherals. In this chapter we look at how this works. You don't need to know this but if you need to modify the library or access features that the library doesn't expose this is the way to go. -

Near Realtime Linux

You can write real time programs using standard Linux as long as you know how to control scheduling. In fact it turns out to be relatively easy and it enables the Raspberry Pi to do things you might not think it capable of. There are also some surprising differences between the one and quad core Pis that make you think again about real time Linux programming. -

PWM

One way around the problem of getting a fast response from a microcontroller is to move the problem away from the processor. In the case of the Pi's processor there are some builtin devices that can use GPIO lines to implement protocols without the CPU being involved. In this chapter we take a close look at pulse width modulation PWM including, sound, driving LEDs and servos. -

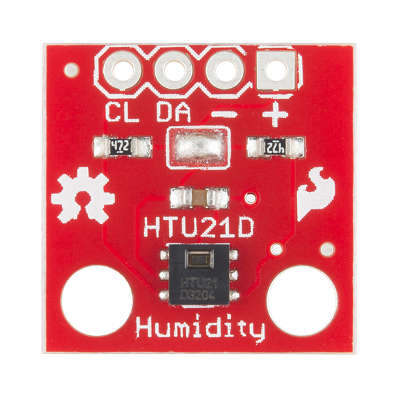

I2C Temperature Measurement

The I2C bus is one of the most useful ways of connecting moderately sophisticated sensors and peripherals to the any processor. The only problem is that it can seem like a nightmare confusion of hardware, low level interaction and high level software. There are few general introductions to the subject because at first sight every I2C device is different, but here we present one. -

A Custom Protocol - The DHT11/22

In this chapter we make use of all of the ideas introduced in earlier chapters to create a raw interface with the low cost DHT11/22 temperature and humidity sensor. It is an exercise in implementing a custom protocol directly in C. -

One Wire Bus Basics

The Raspberry Pi is fast enough to be used to directly interface to 1-Wire bus without the need for drivers. The advantages of programming our own 1-wire bus protocol is that it doesn't depend on the uncertainties of a Linux driver. -

iButtons

If you haven't discovered iButtons then you are going to find of lots of uses for them. At its simples an iButton is an electronic key providing a unique coce stored in its ROM which can be used to unlock or simply record the presence of a particular button. What is good news is that they are easy to interface to a Pi. -

The DS18B20

Using the software developed in previous chapters we show how to connect and use the very popular DS18B20 temperature sensor without the need for external drivers. -

The Multidrop 1-wire bus

Some times it it just easier from the point of view of hardware to connect a set of 1-wire devices to the same GPIO line but this makes the software more complex. Find out how to discover what devices are present on a multi-drop bus and how to select the one you want to work with. -

SPI Bus

The SPI bus can be something of a problem because it doesn't have a well defined standard that every device conforms to. Even so if you only want to work with one specific device it is usually easy to find a configuration that works - as long as you understand what the possibilities are. -

SPI MCP3008/4 AtoD (paper book only)

-

Serial (paper book only)

-

Getting On The Web - After All It Is The IoT (paper book only)

-

WiFi (paper book only)